From Monks to Modernity

Ride through 800 years of history, from the city's humble beginnings to its status as a global hub of culture and technology.

Table of Contents

Foundations & 'Munichen'

Munich’s name comes from 'Munichen,' meaning 'by the monks.' This origin story is still visible in the city's coat of arms, which features a monk. The city was officially founded in 1158 by Henry the Lion, Duke of Saxony and Bavaria, who built a bridge over the Isar River to control the salt trade. As your bus circles the inner city, you might pass remnants of the old fortifications, like the Isartor or Sendlinger Tor, which stood guard over this growing merchant settlement.

In those early days, Munich was a modest market town. But its strategic location near the Alps and on the salt route ensured its prosperity. The layout of the Old Town (Altstadt), which you can explore on foot from several bus stops, still largely follows the medieval street plan, centering on the marketplace that would become Marienplatz.

The Wittelsbach Dynasty

For over 700 years, the fate of Munich was intertwined with the House of Wittelsbach. This dynastic family, which ruled Bavaria until 1918, transformed Munich from a wooden town into a city of marble and stone. As you glide past the Residenz, their massive city palace, you get a sense of their power and ambition. They were patrons of the arts, collectors of treasures, and builders of grand avenues like Ludwigstraße and Maximilianstraße.

Each ruler left their mark. King Ludwig I, for instance, wanted to make Munich 'an Athens on the Isar,' commissioning the neo-classical buildings around Königsplatz. His grandson, the 'Fairytale King' Ludwig II, though famous for Neuschwanstein, was born in Nymphenburg Palace—a major stop on the Grand Circle route. The bus tour is essentially a viewing gallery of their architectural legacy.

Marienplatz & The Heart of the City

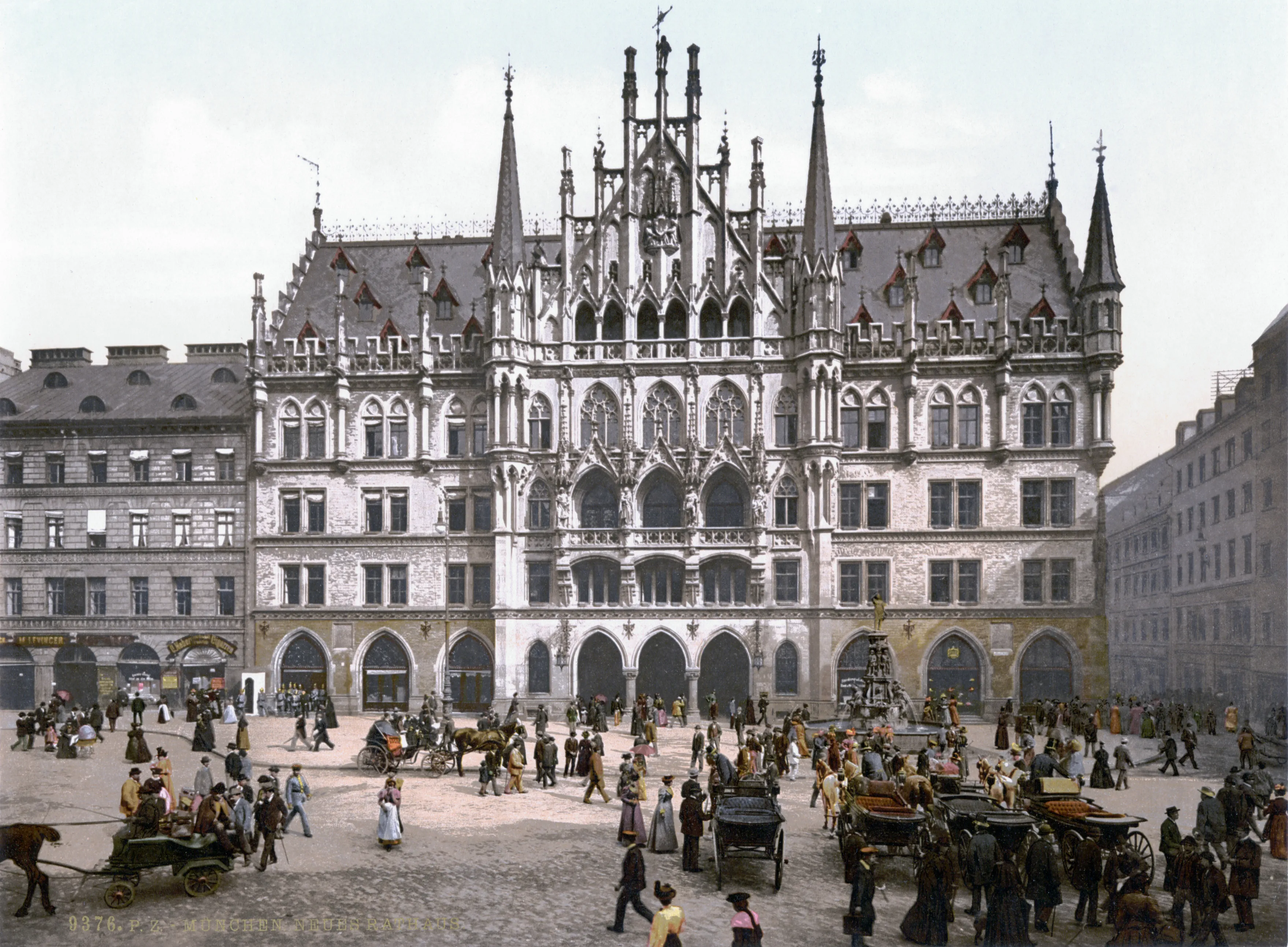

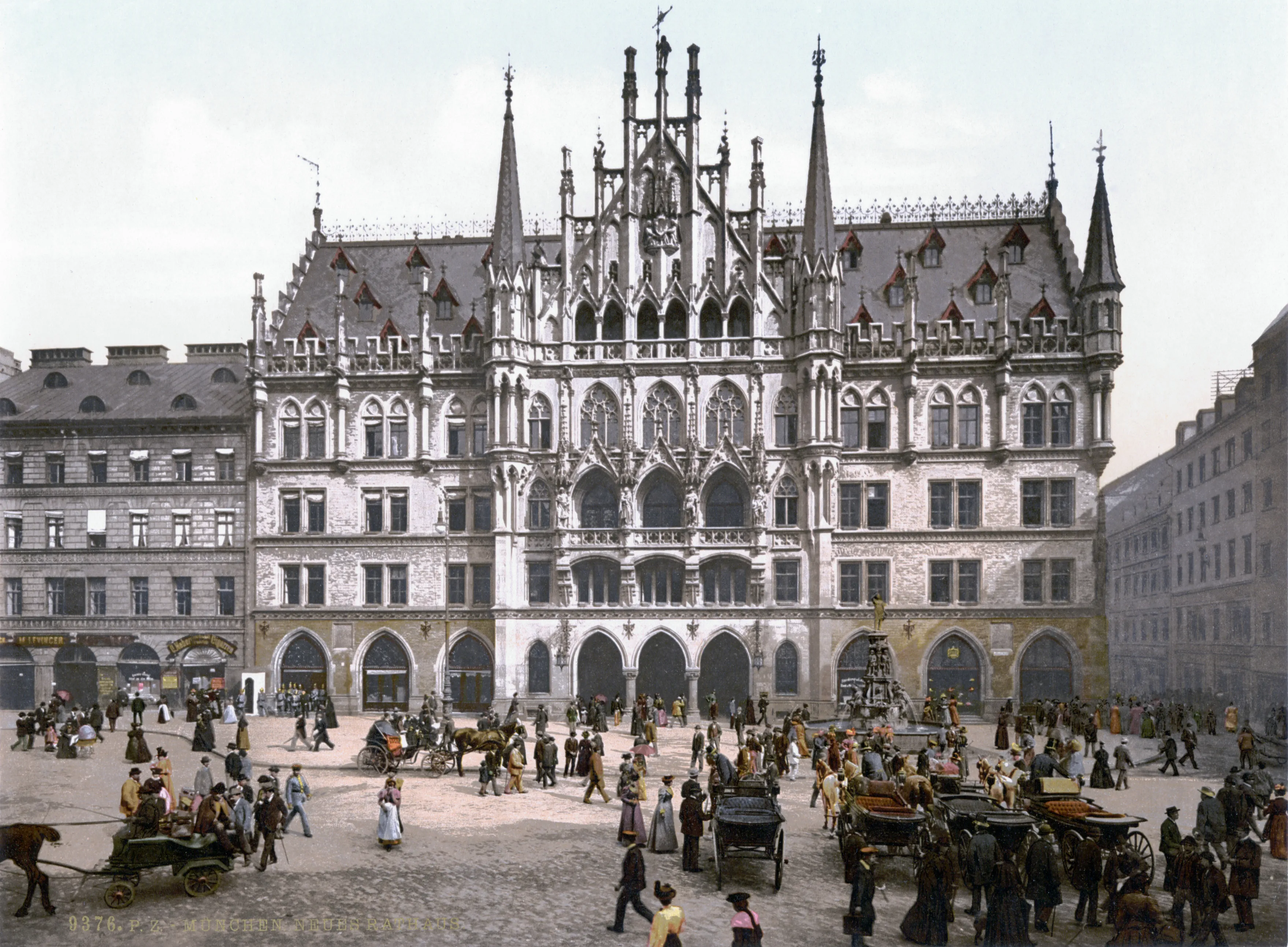

Marienplatz has been Munich's main square since 1158. It is dominated by the New Town Hall (Neues Rathaus), a neo-Gothic masterpiece that looks ancient but was actually completed in the early 20th century. Its famous Glockenspiel draws millions of visitors, re-enacting a royal wedding and the coopers' dance. Hopping off here puts you in the pedestrian zone, steps away from the Frauenkirche, the cathedral with its iconic twin onion towers that define the skyline.

Nearby, the Peterskirche (St. Peter's Church) offers the best view over the city for those willing to climb its tower. This area is always buzzing with life, from street performers to locals rushing through. It serves as the perfect starting or ending point for your bus journey, anchoring your experience in the city's historic core.

Baroque Splendor & Royal Residences

A highlight of the longer bus routes is the trip out to Nymphenburg Palace. This sprawling baroque complex was the summer residence of the Bavarian electors and kings. As the bus approaches the palace, the sheer scale of the canal and the frontal facade is breathtaking. It was built to impress, a Bavarian Versailles surrounded by a vast park that changes with the seasons.

Inside, the Gallery of Beauties and the Stone Hall tell stories of courtly life. Even if you don't enter, hopping off to walk in the palace gardens—among statues, hidden pavilions, and swans—is a highlight. It contrasts sharply with the density of the city center, showing you the leisure lifestyle of Bavaria’s past rulers.

The English Garden & Green Spaces

Munich is one of the greenest cities in the world, and the English Garden is its crown jewel. Larger than New York's Central Park, it stretches from the city center far to the north. Your bus route likely skirts its edge. We recommend hopping off to see the surfers on the Eisbach wave—a unique Munich spectacle—or to enjoy a liter of beer at the famous Chinese Tower beer garden.

The park was created in the late 18th century as a 'people's garden,' a revolutionary concept at the time. Today, it is Munich’s living room. Whether it's sunbathers in summer or snowy walks in winter, the English Garden offers a break from the urban bustle, easily accessible from the sightseeing route stops near the university or Odeonsplatz.

Schwabing: The Bohemian Quarter

North of the city center lies Schwabing. Once a separate village, it became the artistic epicenter of Munich around 1900. Writers like Thomas Mann and artists like Kandinsky lived and worked here. As the bus drives through Leopoldstraße, you'll see the giant 'Walking Man' statue and feel a different vibe—more youthful, more trendy, lined with cafes and pop-up shops.

Today, Schwabing is an upscale residential area but retains its lively spirit. It's a great place to hop off for lunch or dinner away from the tourist crowds of Marienplatz. The architecture here shifts to Art Nouveau (Jugendstil), adding another layer to the city's visual history.

Museums & The Kunstareal

Munich boasts a world-class museum district known as the Kunstareal. The bus route conveniently stops near the three Pinakotheken (Old, New, and Modern), which house European art from the Middle Ages to the present day. You'll also find the Glyptothek (sculpture) and the Lenbachhaus (Blue Rider group) here.

For history buffs, the NS-Documentation Center provides a critical look at Munich's role as the 'Capital of the Movement' during the Nazi era. Hopping off in this district allows you to immerse yourself in culture before rejoining the bus to digest what you've seen while looking out the window.

The Dark Years & Reconstruction

It's impossible to tell Munich's story without acknowledging the dark chapter of National Socialism and the devastation of World War II. Large parts of the city center were destroyed by bombing. However, unlike some other German cities, Munich chose to rebuild its historic landmarks rather than replace them with modern blocks. The Residenz, the National Theatre, and the Town Hall were painstakingly restored.

The bus tour commentary often touches on this reconstruction effort. As you look at the pristine facades, it's humbling to realize that many are 'Phoenixes rising from the ashes,' rebuilt by the determination of the Munich citizens who wanted their 'old' city back.

The 1972 Olympics & Modern Architecture

A major leap into the future happened with the 1972 Summer Olympics. The Olympic Park, with its revolutionary tent-style roofs made of plexiglass and steel, remains a stunning architectural feat and a beloved recreational area. The bus takes you right to the foot of the Olympic Tower.

The park was built on hills made from the rubble of WWII, symbolizing a new, democratic Germany built on the ruins of the past. Today, it hosts concerts and festivals. The nearby BMW Headquarters (the 'Four Cylinders' building) and the bowl-shaped BMW Museum are icons of modernism that stand in stark contrast to the baroque city center.

Oktoberfest & Beer Culture

Munich is world-famous for its beer culture. The Theresienwiese, where the annual Oktoberfest takes place, is a vast open space you might pass. Even outside the festival season (late Sept/early Oct), beer culture is everywhere—in the beer halls like the Hofbräuhaus and the shaded beer gardens.

Beer in Munich is considered a foodstuff ('flüssiges Brot'). The 'Purity Law' (Reinheitsgebot) of 1516 is still held in high regard. Hopping off to enjoy a pretzel and a 'Maß' (liter of beer) under chestnut trees is an essential part of the Munich experience, offering a chance to sit with locals on communal benches.

Industry & Innovation (BMW)

Munich isn't just about history; it's a global economic powerhouse. The presence of BMW is a testament to this heavy industrial heritage. BMW World (BMW Welt) is a delivery center and exhibition space that looks like a giant metallic cloud. It is one of the most visited attractions in Bavaria.

The bus stop here allows you to explore the latest cars and motorcycles for free. It represents the wealthy, high-tech side of Munich—the 'Laptop and Lederhosen' mix that defines the modern Bavarian identity.

Day Trips & The Alps

While the bus keeps you in the city, Munich's location makes it the gateway to the Alps. On a clear day, especially during the 'Föhn' wind, you can see the mountain range from high points like the Olympic Tower. This proximity to nature influences the city's lifestyle—many locals head to the mountains on weekends.

The central bus station (ZOB) and majestic Hauptbahnhof are hubs for trips to Neuschwanstein Castle, Salzburg, or the Concentration Camp Memorial at Dachau. Your hop-on hop-off ticket helps you orient yourself to these transport nodes for future exploration.

Why the Bus Reveals the Real Munich

Munich is often called the 'Village of a Million People' (Millionendorf). It can feel cozy and small in the center, but as the bus takes you to Nymphenburg or the Olympic Park, you realize its true scale. The ride connects the dots between the distinct neighborhoods—the royal, the artistic, the industrial, and the bustling commercial.

Seeing the transition from medieval gates to 19th-century boulevards to 20th-century stadiums in a single loop gives you a coherent narrative of the city. It’s the perfect way to understand how Munich has managed to preserve its deeply rooted traditions while becoming one of Europe’s most livable and prosperous modern cities.

Table of Contents

Foundations & 'Munichen'

Munich’s name comes from 'Munichen,' meaning 'by the monks.' This origin story is still visible in the city's coat of arms, which features a monk. The city was officially founded in 1158 by Henry the Lion, Duke of Saxony and Bavaria, who built a bridge over the Isar River to control the salt trade. As your bus circles the inner city, you might pass remnants of the old fortifications, like the Isartor or Sendlinger Tor, which stood guard over this growing merchant settlement.

In those early days, Munich was a modest market town. But its strategic location near the Alps and on the salt route ensured its prosperity. The layout of the Old Town (Altstadt), which you can explore on foot from several bus stops, still largely follows the medieval street plan, centering on the marketplace that would become Marienplatz.

The Wittelsbach Dynasty

For over 700 years, the fate of Munich was intertwined with the House of Wittelsbach. This dynastic family, which ruled Bavaria until 1918, transformed Munich from a wooden town into a city of marble and stone. As you glide past the Residenz, their massive city palace, you get a sense of their power and ambition. They were patrons of the arts, collectors of treasures, and builders of grand avenues like Ludwigstraße and Maximilianstraße.

Each ruler left their mark. King Ludwig I, for instance, wanted to make Munich 'an Athens on the Isar,' commissioning the neo-classical buildings around Königsplatz. His grandson, the 'Fairytale King' Ludwig II, though famous for Neuschwanstein, was born in Nymphenburg Palace—a major stop on the Grand Circle route. The bus tour is essentially a viewing gallery of their architectural legacy.

Marienplatz & The Heart of the City

Marienplatz has been Munich's main square since 1158. It is dominated by the New Town Hall (Neues Rathaus), a neo-Gothic masterpiece that looks ancient but was actually completed in the early 20th century. Its famous Glockenspiel draws millions of visitors, re-enacting a royal wedding and the coopers' dance. Hopping off here puts you in the pedestrian zone, steps away from the Frauenkirche, the cathedral with its iconic twin onion towers that define the skyline.

Nearby, the Peterskirche (St. Peter's Church) offers the best view over the city for those willing to climb its tower. This area is always buzzing with life, from street performers to locals rushing through. It serves as the perfect starting or ending point for your bus journey, anchoring your experience in the city's historic core.

Baroque Splendor & Royal Residences

A highlight of the longer bus routes is the trip out to Nymphenburg Palace. This sprawling baroque complex was the summer residence of the Bavarian electors and kings. As the bus approaches the palace, the sheer scale of the canal and the frontal facade is breathtaking. It was built to impress, a Bavarian Versailles surrounded by a vast park that changes with the seasons.

Inside, the Gallery of Beauties and the Stone Hall tell stories of courtly life. Even if you don't enter, hopping off to walk in the palace gardens—among statues, hidden pavilions, and swans—is a highlight. It contrasts sharply with the density of the city center, showing you the leisure lifestyle of Bavaria’s past rulers.

The English Garden & Green Spaces

Munich is one of the greenest cities in the world, and the English Garden is its crown jewel. Larger than New York's Central Park, it stretches from the city center far to the north. Your bus route likely skirts its edge. We recommend hopping off to see the surfers on the Eisbach wave—a unique Munich spectacle—or to enjoy a liter of beer at the famous Chinese Tower beer garden.

The park was created in the late 18th century as a 'people's garden,' a revolutionary concept at the time. Today, it is Munich’s living room. Whether it's sunbathers in summer or snowy walks in winter, the English Garden offers a break from the urban bustle, easily accessible from the sightseeing route stops near the university or Odeonsplatz.

Schwabing: The Bohemian Quarter

North of the city center lies Schwabing. Once a separate village, it became the artistic epicenter of Munich around 1900. Writers like Thomas Mann and artists like Kandinsky lived and worked here. As the bus drives through Leopoldstraße, you'll see the giant 'Walking Man' statue and feel a different vibe—more youthful, more trendy, lined with cafes and pop-up shops.

Today, Schwabing is an upscale residential area but retains its lively spirit. It's a great place to hop off for lunch or dinner away from the tourist crowds of Marienplatz. The architecture here shifts to Art Nouveau (Jugendstil), adding another layer to the city's visual history.

Museums & The Kunstareal

Munich boasts a world-class museum district known as the Kunstareal. The bus route conveniently stops near the three Pinakotheken (Old, New, and Modern), which house European art from the Middle Ages to the present day. You'll also find the Glyptothek (sculpture) and the Lenbachhaus (Blue Rider group) here.

For history buffs, the NS-Documentation Center provides a critical look at Munich's role as the 'Capital of the Movement' during the Nazi era. Hopping off in this district allows you to immerse yourself in culture before rejoining the bus to digest what you've seen while looking out the window.

The Dark Years & Reconstruction

It's impossible to tell Munich's story without acknowledging the dark chapter of National Socialism and the devastation of World War II. Large parts of the city center were destroyed by bombing. However, unlike some other German cities, Munich chose to rebuild its historic landmarks rather than replace them with modern blocks. The Residenz, the National Theatre, and the Town Hall were painstakingly restored.

The bus tour commentary often touches on this reconstruction effort. As you look at the pristine facades, it's humbling to realize that many are 'Phoenixes rising from the ashes,' rebuilt by the determination of the Munich citizens who wanted their 'old' city back.

The 1972 Olympics & Modern Architecture

A major leap into the future happened with the 1972 Summer Olympics. The Olympic Park, with its revolutionary tent-style roofs made of plexiglass and steel, remains a stunning architectural feat and a beloved recreational area. The bus takes you right to the foot of the Olympic Tower.

The park was built on hills made from the rubble of WWII, symbolizing a new, democratic Germany built on the ruins of the past. Today, it hosts concerts and festivals. The nearby BMW Headquarters (the 'Four Cylinders' building) and the bowl-shaped BMW Museum are icons of modernism that stand in stark contrast to the baroque city center.

Oktoberfest & Beer Culture

Munich is world-famous for its beer culture. The Theresienwiese, where the annual Oktoberfest takes place, is a vast open space you might pass. Even outside the festival season (late Sept/early Oct), beer culture is everywhere—in the beer halls like the Hofbräuhaus and the shaded beer gardens.

Beer in Munich is considered a foodstuff ('flüssiges Brot'). The 'Purity Law' (Reinheitsgebot) of 1516 is still held in high regard. Hopping off to enjoy a pretzel and a 'Maß' (liter of beer) under chestnut trees is an essential part of the Munich experience, offering a chance to sit with locals on communal benches.

Industry & Innovation (BMW)

Munich isn't just about history; it's a global economic powerhouse. The presence of BMW is a testament to this heavy industrial heritage. BMW World (BMW Welt) is a delivery center and exhibition space that looks like a giant metallic cloud. It is one of the most visited attractions in Bavaria.

The bus stop here allows you to explore the latest cars and motorcycles for free. It represents the wealthy, high-tech side of Munich—the 'Laptop and Lederhosen' mix that defines the modern Bavarian identity.

Day Trips & The Alps

While the bus keeps you in the city, Munich's location makes it the gateway to the Alps. On a clear day, especially during the 'Föhn' wind, you can see the mountain range from high points like the Olympic Tower. This proximity to nature influences the city's lifestyle—many locals head to the mountains on weekends.

The central bus station (ZOB) and majestic Hauptbahnhof are hubs for trips to Neuschwanstein Castle, Salzburg, or the Concentration Camp Memorial at Dachau. Your hop-on hop-off ticket helps you orient yourself to these transport nodes for future exploration.

Why the Bus Reveals the Real Munich

Munich is often called the 'Village of a Million People' (Millionendorf). It can feel cozy and small in the center, but as the bus takes you to Nymphenburg or the Olympic Park, you realize its true scale. The ride connects the dots between the distinct neighborhoods—the royal, the artistic, the industrial, and the bustling commercial.

Seeing the transition from medieval gates to 19th-century boulevards to 20th-century stadiums in a single loop gives you a coherent narrative of the city. It’s the perfect way to understand how Munich has managed to preserve its deeply rooted traditions while becoming one of Europe’s most livable and prosperous modern cities.